Musician

How a world-class jazz violinist went from Lincoln Center to building a business at home

When Chris Howes became a dad, his priorities changed. He traded in his fast-paced, highly successful NYC touring schedule to move back to Ohio and teach music online.

Words by Isa AdneyPhotography by Evan Anderson

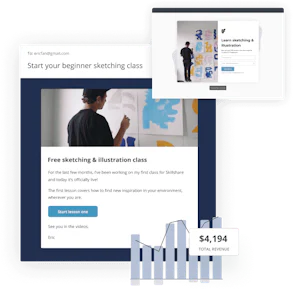

Support your growing business

Kit helps creators like you grow your audience, connect and build a relationship with that audience, and earn a living online by selling digital products.

Start a free 14-day trial

Isa Adney

Isa is the Lead Writer at Kit and an award-winning writer, author, and producer who has profiled incredible creators and artists including Oscar, Grammy, Emmy, and Tony winners. When she’s not writing she’s probably walking her dog Stanley, working on her next book, or listening to the Hamilton soundtrack for the 300th time. (Read more by Isa)